Five years on, impunity for “709” crackdown continues

In the five years since the nation-wide, coordinated “709” crackdown on lawyers and human rights defenders in China, violations against them have continued unabated and with total impunity. Front Line Defenders calls on the Chinese authorities to immediately and unconditionally release all detained or imprisoned human rights defenders, end all forms of legal and extralegal harassment against them, and provide them with redress for the arbitrary detention and other rights violations they and their families have suffered.

Beginning on 9 July 2015, as many as 300 human rights defenders, mostly involved in legal activism, were taken in for questioning by police in a number of cities across China. Whilst many were released shortly after, a number of them were detained for longer periods of time and their families and lawyers were not informed of their whereabouts or physical well-being. All but a few were refused access to their lawyers, with some legal representatives told that this was because their client’s case was related to 'national security'.

Some of the detained defenders, such as Zhou Shifeng (周世锋) and Wang Quanzhang (王全璋), were eventually prosecuted and sentenced to prison terms in unfair trials on trumped-up charges. Others were released on bail after extended periods of incommunicado detention, during which they were subjected to intense interrogation, ill-treatment, and/or forced televised “confessions”, such as in the case of woman human rights lawyer Wang Yu (王宇).

Since 2015, legal and extralegal measures used in the 709 crackdown have continued and become more widespread and systematic, targeting not only human rights lawyers, but also labour rights defenders, citizen journalists, NGO workers, petitioners, and ethnic minorities, especially in Xinjiang. These measures include:

- The introduction of repressive laws and regulations that grant additional unfettered powers to state authorities to restrict civic space, limit Internet freedom, and punish human rights defenders for their legitimate actions and expression, both online and offline. These include the National Security Law (2015), Counter-Terrorism Law (2016), the Overseas NGOs Management Law (2017), Cybersecurity Law (2017), as well as amendments made between 2016 and 2018 to the Measures on the Administration of Law Firms and Administrative Measures for the Practice of Law by Lawyers, Provisions on the Governance of the Online Information Content Ecosystem (2020), as well as the latest National Security Law imposed on Hong Kong a week ago.

- Denial of access to legal counsel of choice has become routine, often on “national security” grounds. Detained defenders or their families are often forced to dismiss their lawyers and accept state-appointed lawyers.

- Holding secret trials, as demonstrated in the cases of human rights lawyers Jiang Tianyong and Yu Wensheng (余文生).

- Surveillance and harassment of family members and supporters of detained defenders.

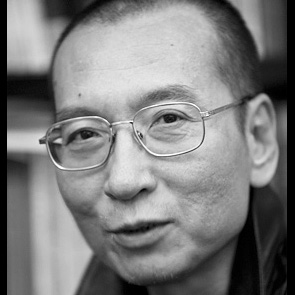

- Denial of access to adequate medical care in detention facilities, which has contributed to the deaths of several defenders, including Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) and Ji Sizun (纪斯尊). Woman human rights lawyer Li Yuhan (李昱函) had her request for medical parole denied in April 2019, despite the deterioration of her health since her detention in October 2017.

- Chinese authorities have pressured foreign tech companies into censoring content, suspending users, or preventing China-based users from accessing circumvention tools in online app stores. Police have pressured and threatened mainland China-based defenders into deleting social media posts on Twitter.

- Human rights lawyers have been disbarred, faced obstructions in renewing their license, or prevented from being hired by law firms after intervention by local judicial bureaus. Other defenders become destitute when they are unable to secure or retain employment or income because of frequent harassment by local authorities.

- Travel restrictions have been imposed on a number of human rights lawyers and defenders, many of whom were only informed of such restrictions at the airport or at a border-crossing. Police justify these restrictions on broad “national security” grounds, without providing any specific details.

- There has been an increase in the use of “residential surveillance in designated location” (RSDL), a measure under China’s Criminal Procedure Law that allows local public security officers to hold human rights defenders accused of “endangering national security” in undisclosed locations for up to six months.

- In cases where defenders face criminal prosecution, each stage of the legal process is often prolonged. Extensions of time limits on criminal detention, prosecution review, convening of trials, and issuing verdicts are routinely approved, resulting in detainees spending an extended period of time between their arrest and obtaining a verdict. For example, woman human rights defender Liu Yanli (刘艳丽) was held under residential surveillance for almost six months before being formally arrested in late 2018; she was only tried in late January 2019 and sentenced 15 months later in April 2020.

- Defenders who were released from detention or from prison after completing their sentence are either subject to strict surveillance or have been forcibly disappeared.

Between 1993 and 2019, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has found China in violation of its international human rights obligations in at least 94 cases, 20 of which occurred between 2015 and 2019. The majority of these cases involved human rights defenders. The Working Group has repeatedly warned China that “widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of the rules of international law may constitute crimes against humanity.” Front Line Defenders is not aware of any Chinese officials who have been held to account for these violations.

Civil society actors inside China have repeatedly called on their government to protect civic space, reform repressive laws, hold abusive officials accountable, and ensure legitimate access to redress. Front Line Defenders has supported and echoed these calls. However, the Chinese government has repeatedly failed to heed them.

The Chinese government’s tendency to clamp down on human rights work and legitimate expressions of concern regarding government shortcomings was tragically illustrated in the critical early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Police intimidated and silenced whistle-blowing doctors, one of whom later died from the virus which he had tried to warn other doctors about.

In light of China’s unwillingness to respect and protect human rights defenders, Front Line Defenders calls on the international community to take decisive and urgent actions by:

- Convening a special session this year at the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) to address widespread and systematic rights violations in China, including reprisals against human rights defenders; and

- Building a coalition to support the establishment of an impartial and independent UN mechanism – such as a UN Special Rapporteur, a Panel of Experts appointed by the HRC, or a Secretary General Special Envoy – mandated to closely monitor, analyse and report annually on the human rights situation in China.