Bringing change, bringing hope

Ana Maria has helped hundreds of Dominicans of Haitian descent reclaim their rights, and resist racism and discrimination. Lorraine leads innovative education initiatives, to raise awareness about environmental rights in communities affected by coal mining in South Africa. Nisha successfully challenged a law discriminating against transgender people in Malaysia, and set up the first organisation providing support to the trans community in her country.

Across the world, women human rights defenders (WHRDs) are bringing about radical changes in their communities. They face immense risks to make their voices heard, to defy oppressive governments, to struggle for justice, and to resist racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and all forms of oppressions.

Ana Maria Belique is one of the leaders of Reconocido, a movement that campaigns for citizenship rights and equality for all Dominicans of Haitian descent, mobilizes and empowers marginalised communities, and accompanies people who need legal support to access their documents.

In the Dominican Republic, Dominicans of Haitian descent are widely seen as second class citizens. In 2010, a new constitution rendered stateless anyone who was born to an undocumented foreign parent. The ruling was implemented retroactively and thousands of people found themselves without valid documents overnight.

Since then, many have been living in limbo: they are denied access to education, employment, health services and the right to vote. In 2010, Ana could not obtain a duplicate of her birth certificate and could not enroll in university because her parents were Haitians, even though she had been registered in the Dominican Republic at her birth.

Ana says that one of her biggest achievements has been bringing young people to the streets, to openly protest against the discrimination they suffer. Haitian descendants from the previous generation were afraid of organising demonstrations and going outside the enclaves they lived in. Yet, step by step, Ana and her colleagues are helping make Dominicans of Haitian descent proud of their origins, and they are building a strong movement that is fighting for real equality and a society where diversity is valued, despite ongoing harassment and intimidation.

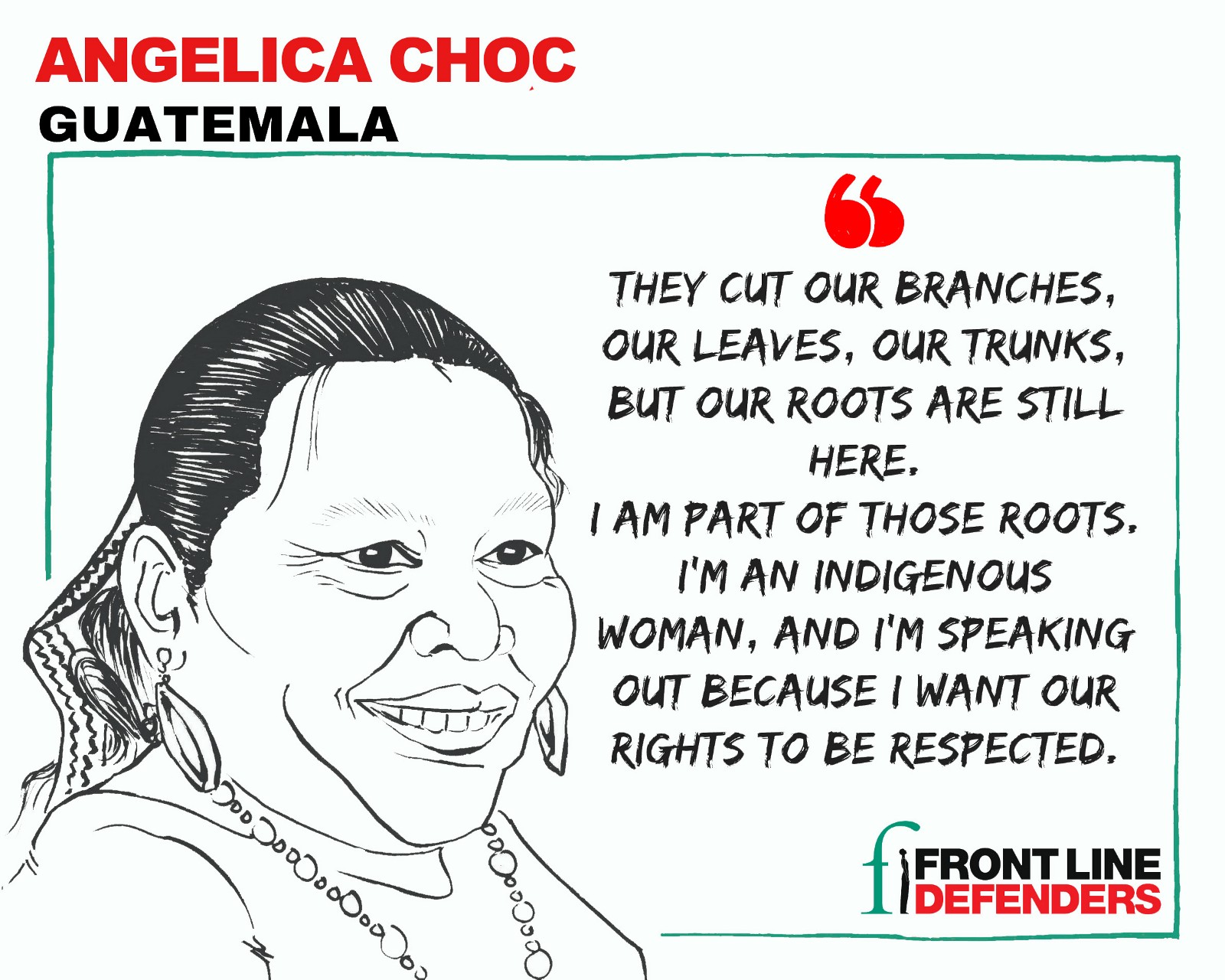

Angélica Choc is an indigenous Mayan Q’eqchi’ defender, from the region of El Estor, in north-eastern Guatemala. Together with her community, she has been reclaiming the right to their ancestral land and protesting against the Fenix mine, one of the largest nickel mines in the country. Despite the risks she faces, Angélica has been speaking out against the human rights violations committed by the mining company. She has campaigned to hold the company accountable and has sought justice both at national and international levels.

In 2006, the mining company evicted local indigenous communities. Private security forces and police officers burned hundreds of houses, attacked villagers, and raped several women in the community of Lote Ocho. Three years later, Angélica’s husband Adolfo Ich Chamán — a prominent community leader and environmental defender — was killed by security guards working for the mining company.

Following her husband’s assassination, Angélica sought justice in a Canadian court, in an unprecedented effort to bring to justice the perpetrators of violent acts of repression against the Maya-Q’eqchi people in El Estor. The case is still ongoing, but it has already set an important precedent. In the past, Canadian courts have only accepted cases related to Canadian companies themselves — not their local subsidiaries.

In March 2015, Angélica also took the lead in a high profile criminal trial in Guatemala against the mining company’s former security chief, Mynor Padilla, who is also a retired Guatemalan army officer. Angélica has challenged the richest and most powerful elites in the country, and she has suffered continuous attacks, threats and intimidation because of that. Yet, Angélica remains strong and resolute in her struggle for justice.

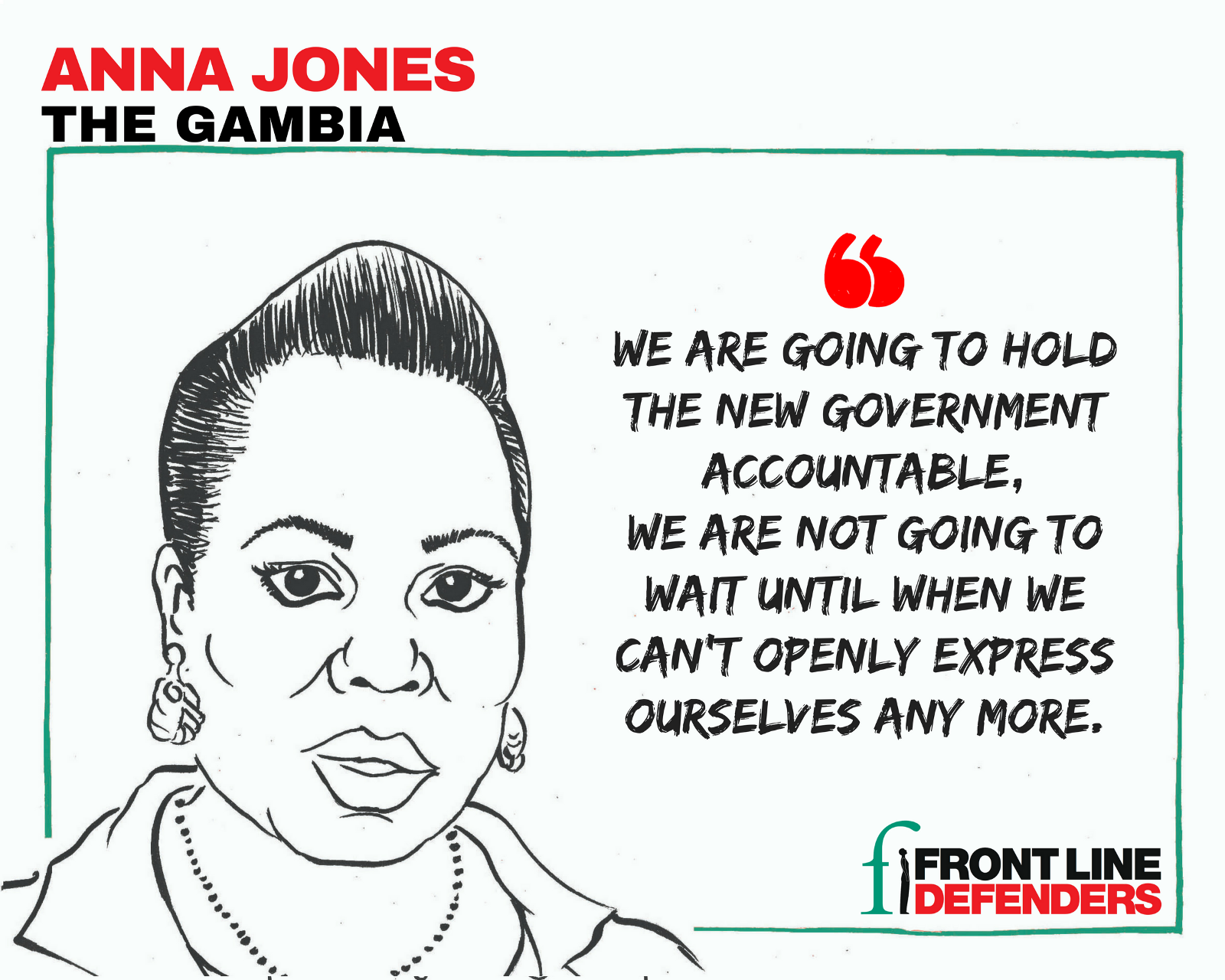

Anna Jones is the National Network Coordinator for WANEP (West African Network For Peacebuilding) in the Gambia. The organisation works to strengthen democracy, prevent conflict, and increase youth and women’s participation in peacebuilding and decision-making.

During the recent presidential elections, in December 2016, Anna and her organisation played a crucial role. WANEP deployed around 150 people to observe the electoral process, and their presence helped validate the results of the elections. Yahya Jammed, who had been in power since 1994, was unexpectedly defeated. After a few weeks of uncertainty and tensions, on 21 January the former president was forced to cede power in what was ultimately a peaceful transition.

After years of repression and attacks against the human rights movement, these elections could mark the beginning of a new era. Yet, there are many challenges ahead. The Gambia has a very patriarchal society and advocating openly for women’s or LGBTI rights can be risky. To challenge this mentality, Anna has led trainings for hundreds of women to build their confidence and support those who want to run for public office. Currently, less than 10 per cent of the parliamentarians are female. Some of the women trained by WANEP, however, are now running for National Assembly elections; no matter the result, their participation is already a major step forward.

Lorraine Kakaza is an environmental rights defender from Carolina, a small town in South Africa’s Mpumalange province, near the border with Swaziland. Lorraine has been raising awareness about the detrimental effects of coal mining in her region.

Despite strict regulations on paper that the coal mining industry in the country is subject to, environmental protection laws are largely ignored. In Lorraine’s region, there are 12 coal-fired power stations and 22 coal mines. This has resulted in high carbon dioxide emissions and heavy metals in the soil and in the water underground. Lorraine says that water in her community is so polluted that it can’t even be used to irrigate the gardens, and provokes skin rashes when used to wash clothes.

In 2013, Lorraine launched a series of podcasts to speak about the problems caused by coal mining and the impact on the everyday live day of local people. She has been repeatedly threatened and harassed because of her efforts to mobilise her community. As part of these efforts to raise awareness, the defender also travels to other communities affected by coal mining, in South Africa and abroad:

“I meet people who have lost hope, but they start believing in me. They realise that if I can make it, then they can make it too. This shows I have an impact in people’s lives, and that we are bringing changes in our communities”, says Lorraine.

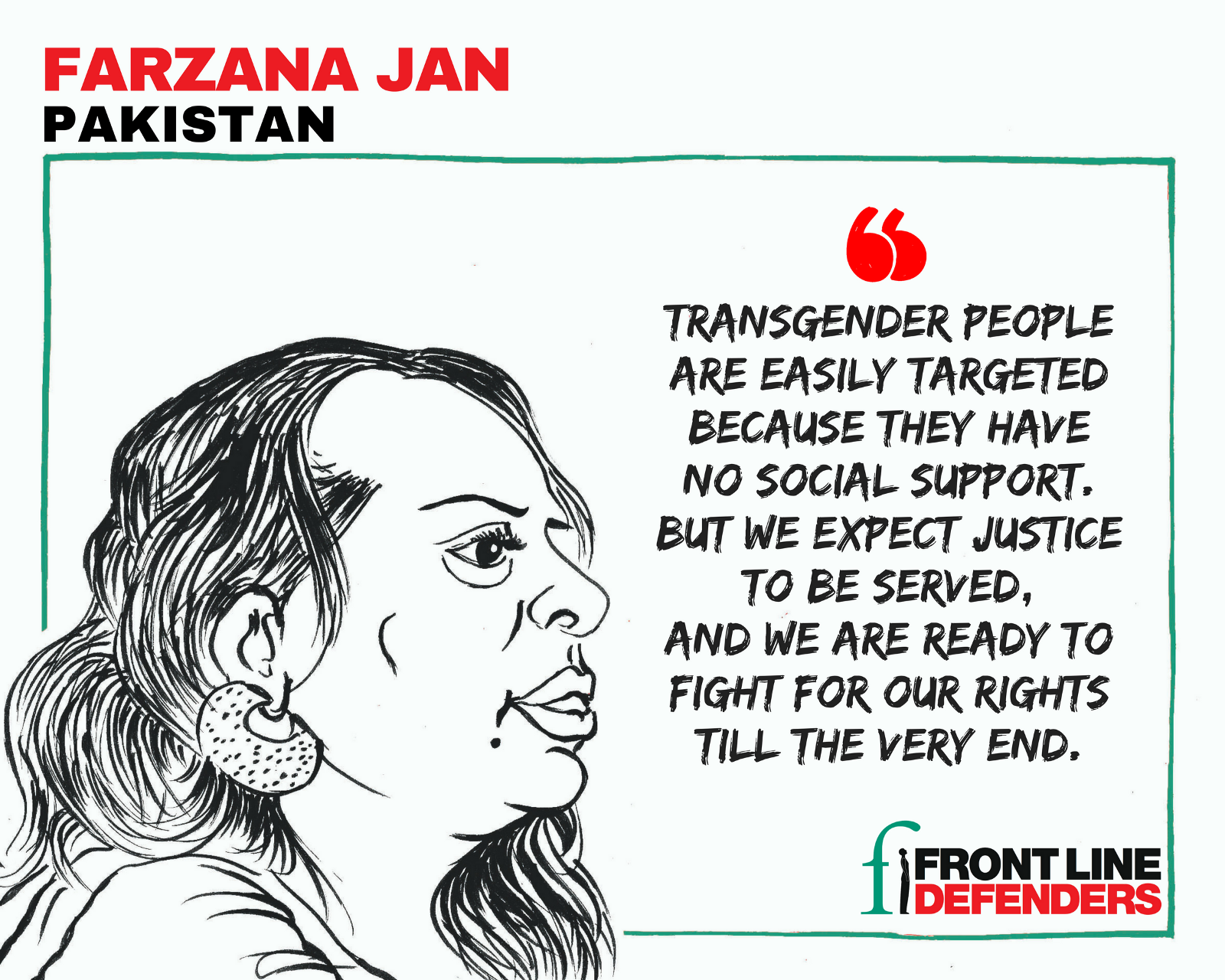

Farzana Jan, also known as the “transgender warrior”, is a trans rights activist from the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in northwestern Pakistan. She is the president and co-founder of the organisation Trans-Action and has been at the forefront of the struggle for trans rights in the country.

Farzana and her organisation have been working to challenge the stigma and discrimination faced by the transgender community in the country, which is increasingly under attack — in the past two years, at least 46 trans people have been killed in Pakistan. Killings were often preceded by threats and violent attacks, which largely went unreported.

Thanks to Farzana and Trans-Action’s tireless efforts, in December 2016 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s provincial assembly unanimously passed a resolution calling on the federal government to ensure voting rights for transgender people. The government also announced it will work on a trans rights protection policy and set up a special committee, to look into the recent wave of attacks, as well as implement protection mechanisms for the trans community.

Thwe Thwe is a farmer and human rights defender who lives in Wethmay village, in northwestern Myanmar. Her community has been deeply affected by the construction of a copper mine, run by the Myanmar military elite and a subsidiary of a Chinese arms manufacturer.

Local authorities promised the community that their land would not be used without consent, that trash and soil from the mine would not be dumped on local farmland, and that any land acquired for the mine would be compensated at or above market value. Four years later, hundreds of villagers have been forcibly displaced or coerced into leaving their land; hundreds more have lost crops and farm animals after contaminated water from the mine ruined land; andpolice have used tear gas and white phosphorous against peaceful anti-mine protests , leaving more than 150 monks and villagers with permanent scars.

Thwe Thwe is educating and strengthening her community’s land struggle. She hands out plainly worded legal advice and statistics on land grabs when she distributes water to local villages, and helps other farmers access the same support networks she has in Yangon. As a result of her activism, she’s been arrested, followed by plainclothes police, and receives regular phone calls from the local police station questioning her about her activities.

Aut Maung, a Burmese poet, referring to Thwe Thwe and another woman leading the protest, said:

“The struggle made them into iron ladies. This is life or death for them — they will defend it at the cost of everything.”

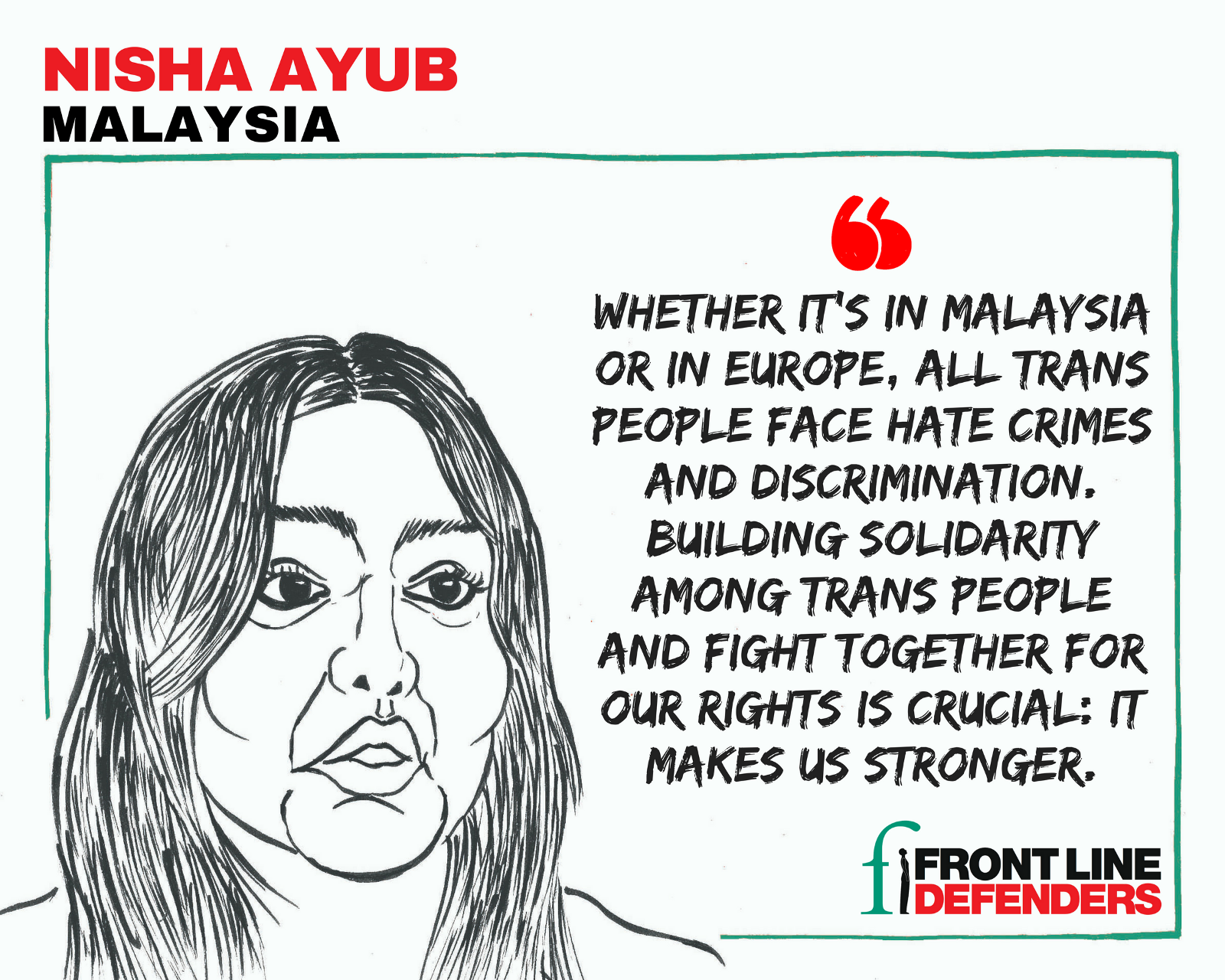

Nisha Ayub is a trans rights defender from Malaysia. She is the co-founder of the SEED foundation, an organisation that provides support to transgender people, sex workers, and people living with HIV and gives them access to health services, shelter and capacity-building trainings. Nisha also leads the group Justice for Sisters, which advocates for trans rights and organises public talks to raise awareness about trans issues. Because of her work, Nisha has been awarded several prizes and in 2016 she became the first trans person to receive the International Women of Courage Award from the US Secretary of State.

The transgender community in Malaysia is faces intense discrimination and violent hate crimes. On February 25, Sameera Krishnan, a young trans woman, was brutally killed.

“We are an easy target. They create fear towards our community, and fear automatically creates hate. Hate crimes are increasing, but many are afraid of reporting them because they feel the police won’t protect them”, says Nisha.

Both as a result of her activism and her gender identity, Nisha has experienced discrimination, threats and attacks on her life. In 2000, she was arrested under a provision of Sharia law that prohibits cross-dressing. She was jailed for three months in a male prison and survived a sexual assault. Once she was released, Nisha — together with other trans activists — presented an appeal against the state Sharia law that was used to imprison her. In November 2014 the Federal Court of Appeals ruled that the law was discriminatory and unconstitutional, and that it deprived trans people of their right to live with dignity. Although the court reversed this ruling a year later, the law has yet to be reapplied and since then no other trans people have been arrested on charges of cross-dressing.

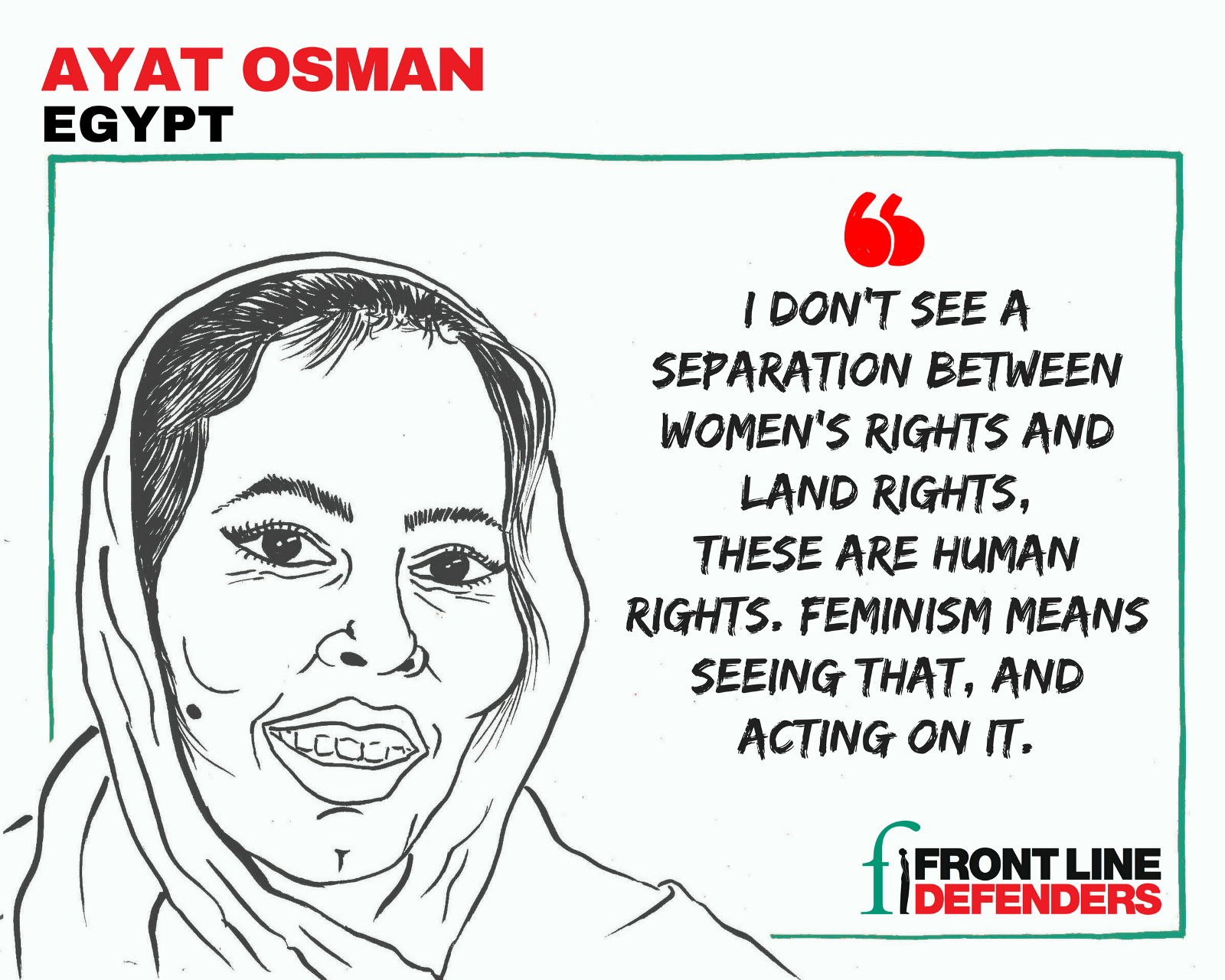

Women human rights defender Ayat Osman and her sister Seham Osman are two of the founding members of Genoubia Hora, the first organised feminist group in Aswan, in south Egypt. They founded the organisation in 2013 in response to what they call “widespread acceptance” of both police violence and violence against women.

Ayat is also a leading member of the Nubian Caravan, a protest movement campaigning for the rights of the Nubian people — an indigenous minority in Egypt — to return to their land. In the early 1900s, Egypt began constructing a set of massive dams near Aswan. By 1970, more than 50,000 Nubians had been forcibly relocated away from their homes on the Nile. They lost their houses, their farms, and their livelihoods.

In November 2016, Ayat and other Nubian rights defenders in Aswan organised a “Nubian Caravan,” driving dozens of cars towards their indigenous Nubian land. As much of their territory has been placed under military control, the Nubian Caravan was caught between a series of check-points and forced to turn back after more than three days in the desert. Female participation in the protest was not large. Still, Nubian women like Ayat and Seham have been at the forefront of the struggle for land rights and the right to return, because women have been those most affected by the effects of mass displacement.

Anna Mokrousova is the co-founder of “Blue Bird,” an organisation that tracks information about civilians kidnapped or disappeared in Eastern Ukraine and provides psychological, legal and humanitarian help to their families.

When the pro-Europe protests, known as Euromaidan, started in Ukraine in November 2013, tensions soon escalated in Donetsk and Luhansk, where Russian-backed separatists clashed with pro-Ukrainian groups. In the midst of fighting, many people were kidnapped or disappeared, mostly by the Russian-backed militias. Almost half of those disappeared are civilians.

A native of Luhansk, Anna Mokrousova herself was kidnapped in 2014. Soon after being released, she received almost 300 requests from friends and acquaintances about people who were disappeared. Since then, Anna has been dedicating her life to helping them: “The experience of being kidnapped has helped me understand what people go through and what kind of help they need,” she says.

Anna and her organisation help the families of the disappeared and civilians who have been released in a number of ways: from establishing contact with militias when possible, to gathering medication and food for the hostages, to providing psychological help and rehabilitation assistance for those released and their families.

Aili Kala is a human rights defender and president of the Estonian LGBT Association. For more than five years, Aili has been advocating for the recognition and the rights of LGBT+ persons, as well as gender recognition for transgender people in Estonia.

The Estonian LGBT Association played major role in passing the Registered Partnership Act in January 2016, also known as the Cohabitation Act, legislation that allows same same-sex and opposite-sex couples in Estonia to register to receive almost all the benefits of marriage.

“It has been a greater cooperation between civil society, NGOs and people who care about human rights and equality,” says Aili.

The Cohabitation Act also allows couples to proceed with second parent adoption. This means that one registered partner can adopt a child of another registered partner.

“Naturally, it is a huge step towards equality and recognition of all people and families,” says Aili.

Since the passing of the act, the number of registered couples and second-parent adoption decisions has significantly increased.