State with an Inhuman Face: How Uzbekistan's Authorities Strangle Human Rights Defenders

In September 2016, the man who had ruled Uzbekistan for 27 years died. As often happens when authoritarians pass on, Islam Karimov’s death after so many years in power left questions as to who would fill the vacuum, and whether the country’s new ruler would ease the repressive practices of the past regime. When Shvakat Mirziyoyev quickly emerged as the successor to Karimov, many in the international community believed that there would be some form of liberalisation. However, since acceding to power, Mirziyoyev has more or less continued the policies that have made Uzbekistan synonymous with authoritarianism.

Mirziyoyev’s government released a number of political opposition figures, some after almost two decades in prison, in what appeared to be an attempt to please Western patrons. But human rights defenders in the country continue to pay a severe price for their work challenging the regime's absolute rule. On 1 March 2017, authorities arrested Elena Urlaeva, one of the country’s most prominent human rights defenders, and forcedly placed her in the Tashkent psychiatric hospital for an undefined period. The detention occurred just days before she was due to meet with officials from the World Bank and International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Where Uzbekistan does appear to be making moves towards reform – such as with the recently announced amnesty decree coinciding with the 24th anniversary of Uzbekistan's Constitution – HRDs seem the notable exception.

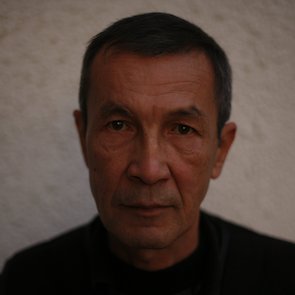

The amnesty decree, for example, did not apply to imprisoned human rights defenders and independent journalists, including Dilmurod Sayid, whose health is deteriorating under harsh prison conditions. Sayid is a member of the Tashkent regional branch of Human Rights Society called “Ezgulik” and worked as a journalist for the “Voice of Freedom” website. He was active in denouncing the corruption perpetrated by Uzbek officials, defending land and labour rights, and criticising the brazen and arbitrary rulings of the government. In February 2009, Dilmurod Sayid was arrested on charges of "extortion" and "manufacturing, [and] forging documents, stamps and seals." He was given a prison sentence of twelve and a half years following a trial that failed to meet international standards. While he was in custody in 2009, his wife and six-year-old son were killed in a car accident on their way to visit him. The same year, he was diagnosed with an acute type of tuberculosis. His petitions for pardon on health grounds have been dismissed, and the Public Prosecutor's Office and Ombudsman continue to ignore complaints related to the grave violation of his right to a fair trial remain. Authorities have denied all pleas for early release or a reduction of his prison term. Dilmurod Sayid is just one of dozens of HRDs in Uzbekistan who have suffered arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and incarceration.

Although three leaders of the political opposition were released since Shvakat Mirziyoyev came into power, the aforementioned continued pressure on human rights defenders indicates the releases are merely symbolic acts to show foreign partners the façade of liberalisation; the government does not yet intend to comply with international human rights law.

Uzbekistan’s international partners have not done enough to demand an end to the persecution of activists inside the country.

During an official visit in January 2017, the EU Special Representative for Central Asia, Ambassador Peter Burian, discussed the “indispensable” role civil society plays in “safeguard[ing] and political rights,” but failed to comment on the array of human rights defenders and journalists arbitrarily detained in the country. The EU-Uzbekistan Partnership and Cooperation Agreement includes a clear clause on respect for the principles of democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, but Uzbekistan is overtly failing to uphold the commitments it made to its people and to the EU.

In recent years , there have been times when the international community has urged the Uzbek government to release dozens of political prisoners, to renounce its systematic harassment of human rights defenders and grave violations of fundamental freedoms, and to abandon its repressive practices, such as torture and the inhumane and degrading treatment of prisoners. However, the European Parliament Resolution on the human rights situation in Uzbekistan (2014/2904(RSP)) that calls for the establishment of a special rapporteur on Uzbekistan at the UN Human Rights Council, as well as widespread criticism of the Uzbekistan government’s failure to comply with its commitments to international human rights law during the Universal Periodic Review of Uzbekistan in 2013, have failed to yield any results. Similarly, no progress seems apparent following the human rights dialogue between the EU and Uzbekistan held in December 2016.

The last hope for HRDs in Uzbekistan is with the international community. Ahead of the next EU-Central Asia meeting of foreign ministers in Uzbekistan in the fall of 2017, as well as the forthcoming high-level EU-Central Asia political dialogue on 'security and counter-terrorism' in Bishkek in May-June 2017, the international community should reiterate to the Uzbek government the importance of the fundamental respect for human rights.