|

OBJECTIVE |

To recognise psychosocial impacts at individual, organisational and community level and understand how they are interrelated with security. |

|

TIMING |

120 minutes |

|

TIME BREAKDOWN |

Introduction - 5 minutes |

|

MATERIALS NEEDED |

Flip charts & marker pens |

When planning and facilitating this session, it is important to consistently apply an intersectional lens to each participant's identity and experiences, and their protection needs. Overlapping systems of discrimination and privilege, such as gender, sexual orientation, religion, disability, racial and/or ethnic origin, economic status/class, marital status, citizenship, age and physical appearance, can have a profound impact on human rights defenders' and their communities' perception of and experience with risks and protection.

|

Notes for trainer: Discussions about psychosocial impacts and well-being might elicit difficult memories and stories from participants. The facilitator should manage the conversation carefully to reduce the risks of re-victimisation and re-traumatisation. Some particular notes for these sessions include:

|

Why do we need to talk about well-being? (5 minutes)

- Because we are constantly exposed to violence (as survivors; as witnesses; as those assisting survivors, etc) in all spaces which we inhabit;

- Because there are certain assumptions around what it means to be an activist (in particular what being ‘a good activist’ means) and in many cases these assumptions centre around ‘sacrifices for the cause’, and ‘in making the struggle the focus of our whole life’;

- Because taking care of our well-being will make the work we do more sustainable;

- Because well-being affects our security.

How have violence and threats impacted you? / What did you do to deal with those impacts? (25 minutes)

Impacts occur on different levels, such as individual, family, organisational/networks and community level.

Brainstorming - the facilitator fills up the matrix based on the ideas from the group.

| Individual | Family | Organisational/ Networks |

Community | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts | ||||

| Responses |

The facilitator should ensure that some of the following key concepts are included in the matrix

- Fear (at all levels)

- Guilt and blame

- Depression

- Distrust

- Conflicts

- Stress/fatigue/burnout

- Traumatic-stres1 including PTSD2

- Vicarious Trauma3

Emphasize that most impacts are normal responses to abnormal events.

Notes for facilitator:

- Some impacts might come up on different levels (individual, family etc).

- Make sure people understand that psychosocial support is not psychotherapy, it is a broad way to look at the impacts of violence and strengthen healthy responses.

- While identifying the impacts, keep in mind that impacts may be experienced differently by different people (see session on Intersectionality).

How are those impacts interrelated with security? (25 minutes)

Being aware of how violence and threats impact us on different levels, recognising it and taking action on it can help us to protect ourselves, continue our work and live in balance.

Examples on how impacts are related to security: fear can cause greater rigidness among members, which often affects communication and can cause conflicts that will have to be taken on before being able to define plans of security or agreeing to measures.

Pairs discussion and feedback to the group in response to the following question and feedback of main issues (15 minutes pairs work and 15 minutes feedback):

What have you noticed about your awareness and responsiveness to security threats when you or your colleagues are feeling under pressure?

Trainer summarizes the pairs' feedback input and adds the following points if they have not come out of the group discussion.

Avoiding thinking deeply about security - Thinking about security means thinking about all the bad things that could happen to us. This can be distressing and exhausting, especially when we have experienced many bad things in the past. Sometimes this results in HRDs not doing sufficient protection planning or doing the planning in a very superficial manner and exposing themselves to risk.

Rigid thinking - When we are afraid we often fall back on default strategies that have worked for us in the past. These strategies may or may not be the best responses to the current situation. When this happens we become resistant to changing or rigid in our thinking about security. This is one of the ways that fear causes conflict within teams. Protection practices should be able to adapt to chaging threats and strategies that our opponents employ.

Too many alarm bells? - For people struggling with traumatic stress and vicarious trauma it sometimes happens that very ordinary things feel dangerous. When this happens fear becomes over-generalised and leads to mistrust between people. When everything feels dangerous (whether it is or not), we become paralysed and it is much harder for us to protect ourselves from actual threats.

Too few alarm bells? - For people who have lived with “too many alarm bells” for too long it sometimes happens that we stop paying attention to all the threats that we feel around us. In this case we end up with “too few alarm bells” and we stop paying attention to important indicators of danger. Again it becomes much harder to protect ourselves from threats.

De-prioritising security measures - Experienced HRDs sometimes de-prioritise security measures in favour of more urgent project deadlines or because they are too exhausted by the work to have to deal with one more energy-consuming activity. It is easy to forget that in some high risk situations, de-prioritising security measures can result in an entire project failing, and in harm to our colleagues and ourselves.

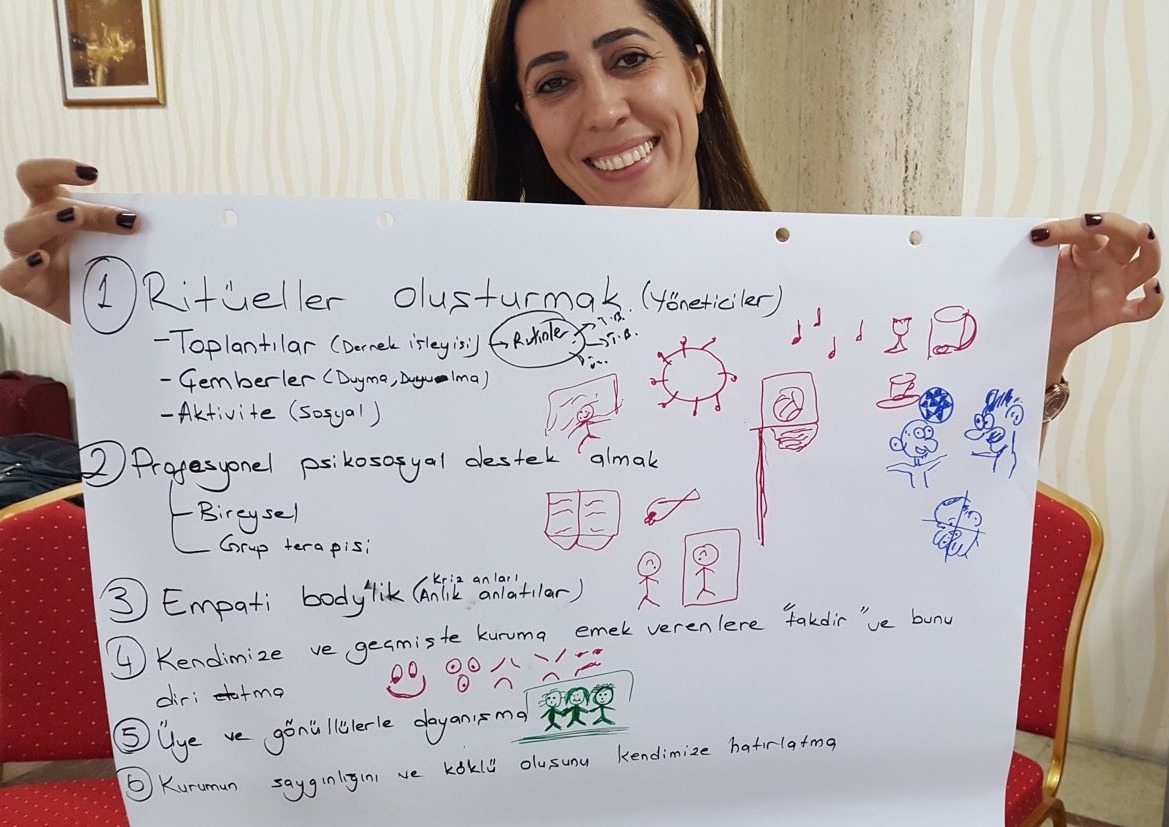

What conditions do you need to be able to implement your protection plan? (30 minutes)

It is important to not only approach security in times of emergency but also, insofar as it is considered strategic, to be able to work on its component of prevention, which not only involves an analysis of the possible risks and scenarios that could be created by the human rights work but also the emotional care and strengthening of the social fabric and identity.

Exercise and sharing

Think of what you would like your organisation and colleagues to offer that would help you implement your protection plan? What are you able to offer to your colleagues and organisation?

I would like my organisation/network to offer:

I would like my colleagues/team to offer:

I can offer:

What I will do for myself:

Resources:

This session has been developed with material from Aluna Acompañamiento Psicosocial, a Mexican NGO, which provides psychosocial support to HRDs and journalists at risk; LevelUP; and Holistic Security by Tactical Tech.

Created by:

Stefania Grasso, Aluna Acompañamiento Psicosocial

Craig Higson-Smith, The Center for Victims of Torture

1There are different definitions of trauma and there are also different situations that bring about traumatic events. In the classic sense, trauma can be understood as a bodily injury or as a situation that causes lasting mental or emotional harm. In the case of human rights violations, we refer to psychological injuries that leave behind negative effects on an emotional, physical, and social level.

2 Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that is triggered by a terrifying event, either experiencing it or witnessing it. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event.

3 “Vicarious trauma is significant emotional wear that is developed by professionals and/or volunteers of healthcare services, emergency services, social/civil protection services, and by all those who generally work with trauma, suffering, fragility, and human vulnerability on a daily basis.” (The quoted text was translated from Spanish for its reference in this publication.) Marlasca, L. (October 15, 2019) El dolor de los otros me abruma: trauma vicario [The Pain of Others Overwhelms Me: Vicarious Trauma]. Centro Psicológico Madrid (Cepsim). Website: https://bit.ly/2Wkgk1l.