1 – Introduction

1.1 A Note for Ines

I met Ines outside an Islamic school in a residential area of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She sat with her legs curled under her listening to Shinta, the transgender woman who founded the school, recite from the Quran. I was there to interview Ines and other human rights defenders about their LGBTIQ+ activism. It was 2017, and we were in the middle of Indonesia’s most violent crackdown on LGBTIQ+ people in decades.

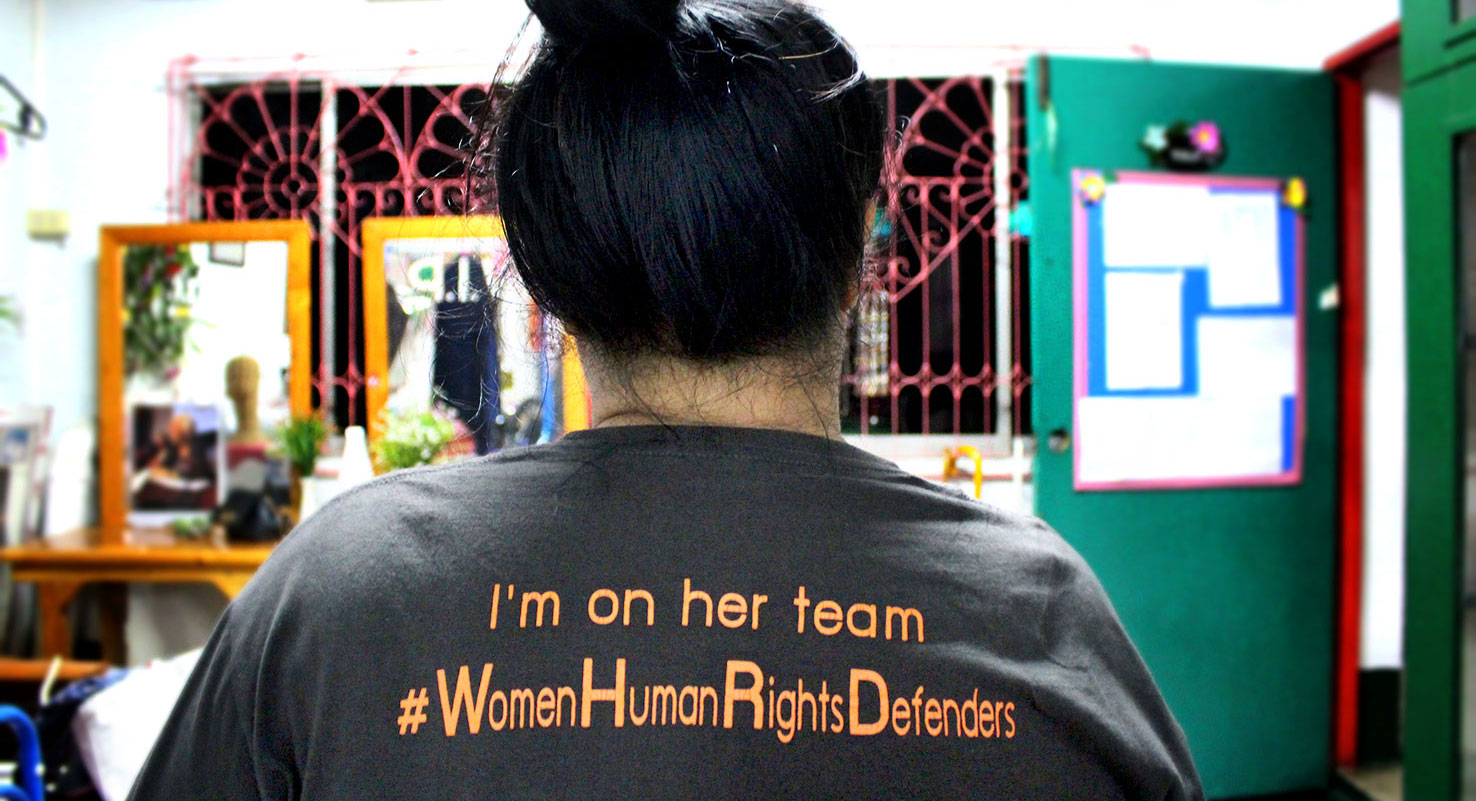

That week, police had arrested 58 people in a raid on a “gay sauna” in Jakarta. They faced ten years in prison. Extremist groups were raiding feminist organisations around the country and attacking activists. Torture and sexual abuse of transgender people by police was rampant in Aceh province. Public canings proscribed by law in the province had begun. Lesbian activists were receiving hundreds of online death threats. LGBTIQ+ rights defenders in every province we visited said they had never been more at risk.

When I asked Ines, a transgender woman, what she needed in order to stay safe as a human rights defender, she simply said “a home.” When I asked what her biggest challenge was, she said if she had one less sex work client per night, she would have more time to protect other women on the street. Ines explained that the time it takes to find clients, go to bookings, and avoid arrest did not leave enough hours in her night to properly coordinate protection for other sex workers.

I did not know Ines sold sex. I did not know to ask.

Ines fled an abusive home as a teenager, shortly after revealing her trans identity to her family. Homeless and sleeping in a train station, she began selling sex to afford food. Inconsistent wages, stigma and limited formal education prevented her and most sex workers in the region from finding safe housing.

The Islamic school we sat outside was ten minutes away from what Ines called “the main prostitution streets in Yogyakarta.” These are the best streets in town for making money and the most likely spot for arrests, physical attacks, and verbal abuse.

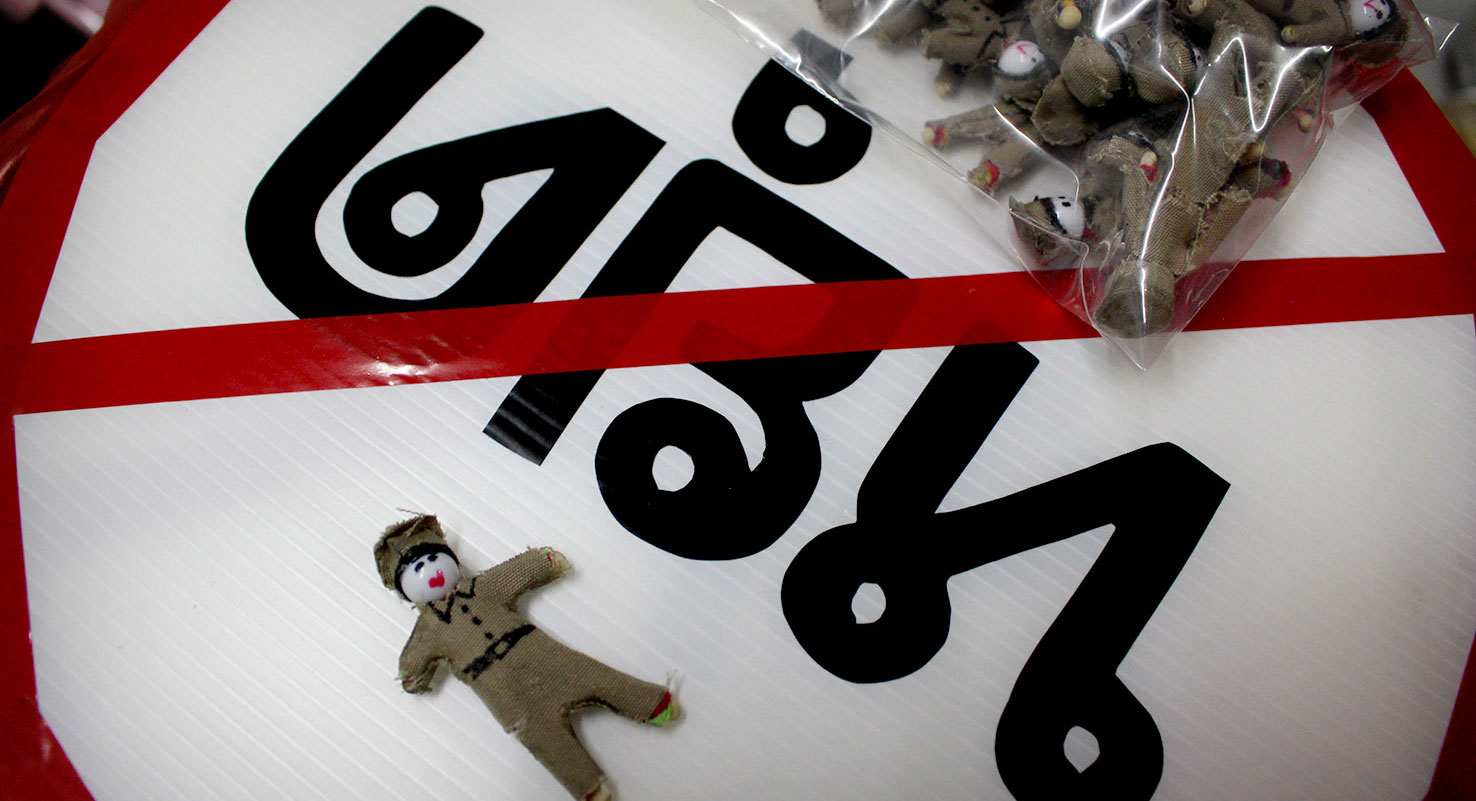

Sex work regulations in Yogyakarta are vague. “Flattery,” “seduction with words, gestures, signs” or other indications that one plans to “carry out indecent acts” are all criminal. The regulations say sex work will “reduce a person’s honour” and conflict with Indonesian values. Local workers say police enforce these regulations primarily by temporarily detaining and assaulting sex workers.

Workers who speak up for one another during these attacks are often targeted by name the following night. Being a community advocate makes sex work more dangerous.

Ines is one of those advocates. She develops security and protection strategies for other sex workers in Yogyakarta. For a decade, she split her nights between taking her own clients and managing a protection network of other sex workers in town. They track each others’ locations to prevent disappearances and kidnapping, collectively “blacklist” abusive clients, and share new security strategies.

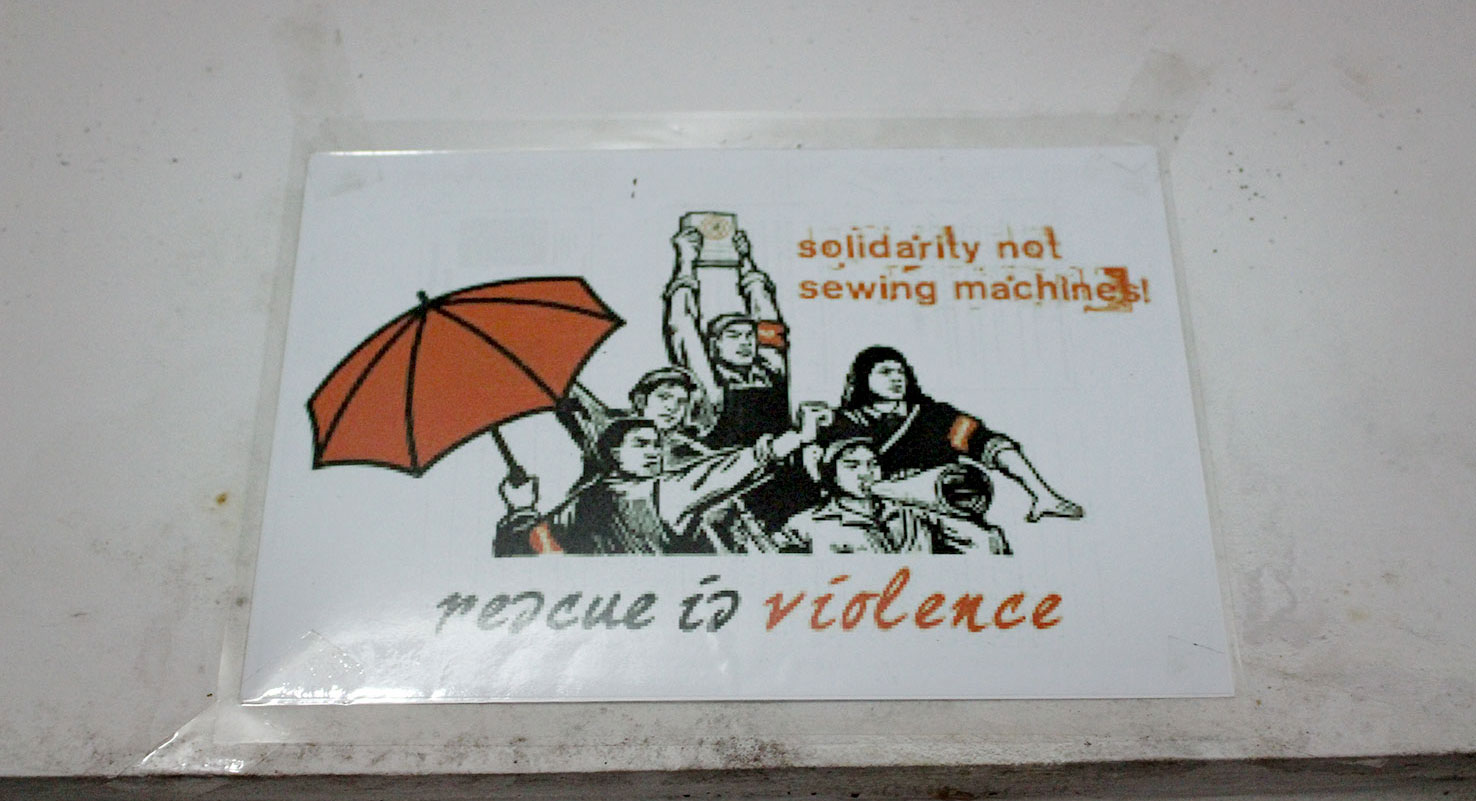

Ines’ group advocates for services that individual sex workers are denied. They successfully won the right to access housing, pooling their wages to circumvent Yogyakarta’s “stable salary” rental requirement. When one worker is sick, others work extra to feed her. Ines trained herself in the languages of health and human rights because hospitals routinely turn away sex workers. Many are denied emergency care after brutal assaults, and some clinics simply refuse to treat transgender women. Ines learned the phrases and concepts that gained sick sex workers access to hospitals. When her friends were harassed, beaten, or denied access to life-saving HIV treatment, they called Ines.

“We got good at collective advocacy. We realized the government was more likely to listen to a group with a name than an individual transgender woman. So we started with the hospitals, then applied the same strategy to fight for transgender women in government detention centres who had no access to health or legal services.”

Ines said the biggest threat to her activism was poverty. With a few more hours each night – two or three less clients, Ines estimated – she could properly track the other women, document violence and file police reports. But taking fewer clients is not something Ines could afford to do.

“On the street at night, I can’t focus on anything except making money, because I have to eat. If I had a bit more money, I’d still go to the street. This is where my community is. But if I didn’t have to focus completely on clients, on making enough money to eat tomorrow, I could devote more time and brain space to security and protection for the other women.”

Ines was gendered male at birth. Since the day she ran away from home, 15 years before I met her, Ines dressed, applied makeup, and styled her hair “like a girl.” She told me she wore “gorgeous” dresses for both human rights meetings and to sell sex. But as she became better known across Yogyakarta for her advocacy, police began to pay more attention to her at night.

“I looked the same at daytime meetings as I did on the street. Police recognized me immediately among the other transgender women. They singled me out, abused me, took my photo, and followed me. I’m in more danger than the other sex workers because of my visible activism. And I’m in more danger than other activists [who are not sex workers] because when they go home at night, I go to the street.”