40 years after CEDAW ratification, women human rights defenders in China still face reprisals

Forty years after China ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) on 4 November 1980, women human rights defenders in the country continue to face many forms of undue restrictions and threats. Front Line Defenders calls on the authorities at all levels in China, as well as business enterprises, to take all necessary measures to respect and protect their legitimate and peaceful promotion and defence of human rights and gender justice.

Women human rights defenders in China work for the realisation of a wide range of human rights. They defend workers’ rights and advocate against sexual harassment. They campaign for greater public participation of individual citizens and independent civil society in the Chinese government’s reporting to UN human rights mechanisms. They conduct public education, launch strategic litigation, and engage lawmakers to reform laws, policies and practices that discriminate against persons based on sex, sexual orientation and gender identity, including in the areas of marriage, employment, and health services. They support victims of domestic violence to seek accountability and rehabilitation. They mobilise youth to campaign for urgent actions to tackle the climate crisis. They also advocate for stronger oversight and regulations of outbound Chinese investment and loans, Chinese companies’ operations overseas, and official development assistance to ensure better human rights and environmental protection and a gender-responsive approach in countries that host Chinese investment and businesses.

As lawyers, women human rights defenders fight for fair trial rights for political dissidents and human rights defenders who face judicial harassment. As independent journalists, they document and report on rights abuses often glossed over or ignored by State media, including the suffering of residents in Wuhan during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. As diaspora members or survivors of widespread and systematic violations in Xinjiang and Tibet, they brave the risks of reprisals to expose atrocity crimes committed against minorities. As defenders, they continue to challenge patriarchy, gender-based violence and sexual harassment within civil society.

In its conclusions after an official mission to China in 2013, the UN Working Group on discrimination against women in law and practice emphasized that “the goal of gender equality cannot be fulfilled in China unless women’s rights defenders can function in an environment of freedom” and called on the government to provide “legal protection for all defenders of women’s human rights and autonomous women’s groups and coalitions in civil society to allow them to advance implementation of the law and advocate for policy changes affecting gender equality as part of the overall strengthening of the rule of law, democracy and human rights.”

In November 2014, the CEDAW Committee, the UN body that monitors compliance with the Convention, urged the Chinese Government to take “all necessary measures to protect women human rights defenders”. China’s next report to the Committee has been overdue since 1 November 2018.

During the previous three cycles of Universal Periodic Review, China repeatedly said it supports and has implemented recommendations urging it to create a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders, including those in Hong Kong, so that they could exercise their fundamental freedoms without fear of reprisals.

To date, these important recommendations remain unimplemented. Women human rights defenders, and often their family members, continue to face police harassment, internet censorship and online smear campaigns, defamation lawsuits launched to silence victims of sexual harassment, surveillance, restrictions of movement and travel bans, denial of employment or education, prolonged arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, prosecution, and imprisonment. These trends are illustrated by the following emblematic cases:

- Chen Jianfang (陈建芳), a land rights defender and an advocate for greater citizen participation in China’s human rights reporting to UN mechanisms, has been in arbitrary detention in Shanghai since March 2019 without access to legal counsel of her choice. Her detention came one day after publishing an online tribute marking the anniversary of the death of fellow woman human rights defender Cao Shunli in police custody in 2014. She was indicted in September 2019 for “subverting State power” and her current whereabouts and the outcome of her prosecution are unknown.

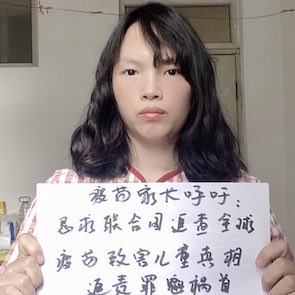

- He Fangmei (何芳美), a vaccine safety advocate, was in arbitrary detention for 10 months between March 2019 and January 2020. She is believed to have been detained at an unknown location in Henan province since 10 October 2020 after conducting a non-violent ink-splashing protest in front of a government office the day before.

- Li Yuhan (李昱函), a human rights lawyer known for defending other defenders facing judicial harassment, has been in arbitrary detention since October 2017 with deteriorating health. She was indicted in April 2018 but a trial has yet to be held.

- Liu Yanli (刘艳丽) was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in May 2020 for her online criticisms of Government leaders and policies as well as her writings on democratic reforms and on state corruption.

- Spouses of human rights lawyers who are detained have become defenders themselves and continue to face harassment, surveillance and restrictions, including recent actions affecting Xu Yan (许艳) and Wang Qiaoling (王峭岭).

- Zhang Zhan (张展), a former lawyer and citizen journalist outspoken about human rights violations, disappeared in Wuhan in May 2020 after conducting independent reporting about the COVID-19 outbreak, and resurfaced in police detention in Shanghai. She was indicted in September 2020 and is now awaiting trial.

- Hong Kong women human rights defenders Agnes Chow Ting (周庭), Chow Hang Tung (鄒幸彤), Margaret Ng Ngoi-yee (吳靄儀) are among the pro-democracy figures in the city facing charges for their political expression and/or participation in peaceful assemblies calling for democratic reforms or commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

- In the UN Secretary-General’s latest report on reprisals against human rights defenders who cooperate with UN human rights mechanisms, 9 out of 17 human rights defenders in China highlighted in the report were women.

In its latest report to the UN committee responsible for monitoring compliance with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Chinese government admits that “gender stereotypes and inequality between men and women persist, and violations of women's rights” continue to occur.

On 1 October 2020, in a speech before a high-level UN gathering commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women, which was held in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping said China is “prepared to do even more” to advance women’s rights worldwide and urged the world to “eliminate prejudice, discrimination and violence against women and make gender equality a social norm and moral imperative observed by all.”

On 29 October 2020, at the end of the fifth plenum of its 19th Central Committee, the Chinese Communist Party promised to, amongst other goals, build a “country based on the rule of law” and guarantee the protection of the “rights of citizens to equal participation” by 2035.

Front Line Defenders takes note of the Chinese Government’s own recognition of both the importance of gender equality and the persistent challenges the country still faces in this area. It urges the Chinese government to match its words and commitments with concrete, rights-compatible actions to respect and protect all human rights defenders who are working to advance women’s rights, including by:

- Immediately and unconditionally releasing all women human rights defenders detained or imprisoned solely for their legitimate and peaceful work in defence of human rights, including Chen Jianfang, He Fangmei, Li Yuhan, and Liu Yanli;

- Ceasing and refraining from all forms of harassment and undue restrictions on the enjoyment by women human rights defenders of their rights to freedom of expression, association, assembly, movement, and religion or belief;

- Investigating in an independent, impartial, and credible manner all allegations of threats and harassment against women human rights defenders by State authorities and bring to justice those responsible in accordance with international standards;

- Conducting a comprehensive legal review of existing laws, policies and practices to identify and rectify inconsistencies with international human rights standards, including provisions used to target women human rights defenders